Creating Great Choices: A Leader’s Guide to Integrative Thinking

by Jennifer Riel and Roger L. Martin

Conventional wisdom says that trade-offs are inevitable when making hard choices. But settling for the least bad option is a lousy way to make a big decision. This book proposes a “third and better way” to make important choices using proven, repeatable processes to create better answers to problems, sidestep our built-in biases, and avoid trading off one stakeholder group’s needs for another.

This book builds on co-author Roger Martin’s previous book, The Opposable Mind, which introduced us to integrative thinking. Creating Great Choices extends that exploration, building out the methodology for making decisions in challenging situations by embracing (as opposed to ignoring) opposing ideas. Using the tension between those opposing forces to develop a new solution superior to the original options. Integrative thinking is about making smarter choices by developing new options rather than settling for the least objectionable of the original options—which is what most of us do most of the time.

Creating Great Choices is organized into two sections. Part 1 outlines how we traditionally make decisions and why we make poor choices. It introduces integrative thinking as a better approach to making better choices. Part 2 covers the four steps that make up the integrative thinking process. The book concludes with a chapter on “stance” (our way of being in the world) and the path to becoming a more integrative thinker–a better decision-maker.

In the authors’ words, the “process makes up the heart of this book… is a methodology for problem-solving that… enables all leaders to leverage the tension of opposing ideas to create transformative new value.”

About the Authors: Jennifer Riel is an author and adjunct professor at the University of Toronto’s Rotman School of Management, where she teaches integrative thinking and innovation. She also serves as a strategy and innovation adviser to senior leaders at several Fortune 500 companies. She has written for the Globe and Mail, Businessweek, Huffington Post, and Fortune.com.

Roger Martin is a Professor Emeritus at the Rotman School of Management, where he served as Dean from 1998-2013. He advises CEOs on strategy, design, and integrative thinking and has published 13 books and 30 Harvard Business Review articles. Businessweek named him “one of the ten most influential business professors in the world” in 2007. In 2017, he was named the world’s #1 management thinker by Thinkers50, a biannual ranking of the most influential global business thinkers.

This summary reflects my takeaways from a useful book I recommend to others. Reading a summary isn’t a substitute for reading the book. There’s much more than I can cover here. Plus, this is my interpretation. If these ideas resonate with you, I encourage you to get a copy from your favorite bookseller. Here are the Amazon links: e-book | Audio | Print

Unless otherwise noted, all quotes should be attributed to the book’s authors.

SUMMARY

Conventional Decision Making

When faced with a tough decision:

- We make a choice rather than create a solution. We choose the least objectionable of the available options instead of finding a better solution. Our worldview and decision-making tools make trade-offs seem natural, but there is rarely a single solution to satisfy everyone. So we make unsatisfactory compromises, argue with others, struggle to decide, and delay meaningful action. We seek “a mythical right answer but find only suboptimal choices and compromises.” Integrative thinking is about taking the time and using a process to create an option that is superior to the original ones.

- We optimize among bad choices. We traditionally view decision-making as an optimization problem–a tradeoff between options, finding the point between choice “A” and choice “B” that we can live with. The process of integrative thinking is more ambitious. It’s taking the best of choices “A” and “B” and creatively reconfiguring them to create a new option that meets the need better.

- We rely on mental shortcuts. We view the world through mental models, shortcuts that frame our decision-making and thinking. This can lead to implicit, narrow, and flawed problem-solving approaches and an insular mindset that discounts other perspectives. Integrative thinking can help to mitigate these limitations and improve decisions.

We rely on mental models that are useful, necessary, and flawed.

Our mental models–the set of models our minds create of the world–accumulate over time and ultimately become our reality. The modeling process happens automatically, continuously, and, for the most part, subconsciously.

Rather than being a window into the world, the human mind is a filter. It filters out a lot of complexity and creates a simplified picture. Automatic subroutines allow us to pay attention to some things and not others and make sense of our experiences. These mental models are essential to living in a complex world without being overwhelmed. But…

Our mental models are:

- Incomplete. Mental models are simplified representations of reality–they leave things out. But, over time, our mental models of the world become our reality. Because of this and how we use them, mental models can lead to poor decisions.

- Implicit and automatic. They’re automatic, so we are usually unaware that we’re using them, making it harder for us to understand why we act the way we do and achieve the results we do. Unarticulated models and unsurfaced assumptions often cause poor decisions.

- Easily manipulated. Outside factors, such as the environment and other people, impact our mental representations. This can explain our apparent irrationality when we do one thing, then another, under seemingly similar circumstances but different influences.

- Sticky. Personal, vivid, and recent events shape our worldview, making it hard to change. It’s easier to find answers that support our worldview than to challenge it. Contrary evidence can strengthen our beliefs, known as the “backfire effect.”

- Simplistic. The mind seeks efficiency and builds overly simplistic models of reality, kept simple by cognitive biases. If our models fail, we often blame the world. We ignore side effects as irrelevant, so our models don’t improve. And oversimplifying models can lead to overconfidence in them. When we simplify, we may ignore salient information and suppress dissenting views, leading to poor decisions.

- Narrow. We overestimate the extent to which a model that works in one situation can also work in another. Models are built for a specific context but are frequently overextended to multiple contexts, becoming less fit for purpose as they are used outside of their original application.

- Singular. Once we settle on a model, it feels like the right answer. But the world naturally produces different models of the same thing in different people’s heads. School teaches us that our job is to find the correct answer and make the wrong one disappear.

- Unavoidable. Since we develop them automatically, our models are unavoidable. But we can become aware of them and their shortcomings. It takes conscious effort.

Cognitive biases exacerbate the problem.

All decision-making is subject to cognitive biases, which are systematic dispositions or inclinations in our reasoning that we are unaware of, leading to “flawed patterns of responses to judgment and decision problems” according to the Encyclopedia of Human Behavior (Second Edition), 2012

Two cognitive biases are prevalent and pernicious in decision-making:

- Affinity bias is the tendency to spend more time with people like us and hire and promote them because we feel more comfortable around them. In decision-making, when someone disagrees with us, we shut them down instead of trying to understand them.

- Projection bias is when we think that everyone else thinks like us.

An organization’s decision-making culture isn’t much help.

Decision-making is usually a linear process reliant on mental models and subject to unchallenged biases. A narrow process leads to “a narrow answer based on a simplified view of the world, while simultaneously allowing us to feel that we have been rigorous and evidence-based in our methodology.”

We need decision-making cultures and processes that proactively seek divergent points of view and see disagreements as resources. If we continue to see our job as finding the correct answer and trying to get others to buy in, we will look for easy compromises and accept suboptimal trade-offs. We can make better decisions by considering our mental models and avoiding our biases. To do this, we need a different way of thinking. And that different way of thinking needs a process.

Three ingredients are missing in business-as-usual decision-making.

Metacognition, empathy, and creativity can improve our decision-making processes. They are missing ingredients in most of our approaches, but when combined, they lay the groundwork for more informed choices.

1. METACOGNITION–Paying attention to our thinking and what’s influencing it.

Metacognition can be defined simply as “thinking about thinking,” or more formally as “…one’s knowledge concerning one’s own cognitive processes or anything related to them,” according to developmental psychologist John Flavell who coined the term. The process involves both awareness and discipline.

It’s a skill that can be improved with time, practice, and feedback. Unfortunately, most of us have had no formal training in metacognition. Since most of our educational systems focus on the “what” rather than the “how” of learning, most leave school without being taught to evaluate our ideas critically.

Awareness and discipline can help us recognize and understand what’s underlying our choices: our mental models and their pluses and minuses and our biases and their influences. And recognize that others may view the problem (and solutions) differently than we do.

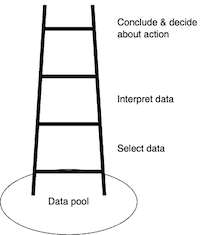

The Ladder of Inference

The book uses a streamlined version of Chris Argyris’ “Ladder of Inference.” It’s a simple but handy tool representing the thinking process as a set of rungs on a ladder. Outlined in the book as four “rungs”:

- Data pool. Because of the large data pool, we focus on only a tiny portion.

- Select data. We choose data (partially subconsciously) based on our experiences, needs, and biases.

- Interpret data. We analyze data and try to make sense of it. We interpret data, draw conclusions, and build models using logical inferences. These conclusions cover many beliefs.

- Conclude & decide. We make choices based on our models and conclusions.

The ladder of inference can help you clarify your thinking which is integral to integrative thinking. If we explicitly state our data and reasoning and challenge ourselves to understand our conclusions, our logic will be more precise and our conclusions richer.

Because our thinking is automatic, implicit, and abstract, we need tools and frameworks to create the awareness and discipline that helps us understand the thinking behind our choices and the choices of others. Better ladders of inference require meaningful curiosity and empathy for others.

2. EMPATHY–Considering other people’s viewpoints (even when they disagree).

Empathy is appreciating another person’s thoughts, feelings, and experiences. Recognizing the viewpoints of others helps us to see the gaps in our thinking and opens up opportunities for collaboration. It doesn’t mean agreeing with or endorsing them; simply appreciating and understanding.

Empathy comes naturally. Basic forms of empathy occur automatically in the human brain through mirror neurons.

The affinity bias makes empathizing challenging. Our cognitive biases come into play, particularly the affinity bias, which makes it easier to feel empathy for people like us and more difficult to empathize with members of other groups. It’s a given that this bias is the root of many problems.

What’s needed is deliberate empathy. To leverage the diversity of views, we must be curious about others and want to see the world as they do. We also need deliberate processes and tools.

Tools borrowed from design thinking can help. Designers use empathy to understand the end-user when designing a product or service. It begins with a deep dive into the user’s context, behavior, and experience:

- Observation. Watching how others behave.

- Engagement. Getting others to tell their stories. Stories are powerful.

- Experience. Experiencing what others go through.

Empathy is two-way. Demonstrating empathy helps others feel empathy for us. People are more curious and open with you if you are curious and open with them. It’s the “reciprocity” norm–people feel obligated to return favors.

3. CREATIVITY–Taking the time and having the courage to look beyond the ordinary.

Creativity is simply seeking new, better answers rather than relying on what is available.

Creativity isn’t the domain of the lone genius. No one is born creative, and it is not a solitary endeavor. It requires teamwork and effort. It’s a skill that each of us can develop.

Being creative is about giving yourself permission to try. The biggest impediment to creativity is fear of embarrassment–of being judged. It keeps us from sharing ideas, taking on new projects, and learning new things. For better decisions, we need to give ourselves that permission and create environments where our teams experience that permission as well.

Here are five guidelines that can help:

- Frame the problem to be solved. A detailed description of the issue is both an inspiration for new ideas and a benchmark for potential solutions. Design thinking’s core question, “How might we…?” is the source of its magic. Great answers come from straightforward questions.

- Don’t start with a blank slate. Creativity is about connecting and recombining ideas.

- Value bad ideas. Suspend judgment because even the most outlandish ideas often contain the germ of a breakthrough.

- Construct to think. Designers create quick prototypes and use storyboards, role-playing, and narrative storytelling to develop new ideas because abstraction hinders the creative process.

- Take your time. Rushing puts a damper on creativity. Letting your mind wander, play, and think of other things is essential.

A richer decision-making process changes our job from choosing an option to creating a better solution.

Integrative Thinking

“integrative thinking is the ability to constructively face the tensions of opposing models, and instead of choosing one at the expense of the other, generating a creative resolution of the tension in the form of a new model that contains elements of the individual models, but is superior to each.”

To put integrative thinking to work in our decision-making processes, Riel and Martin outline four stages:

- Articulate opposing options

- Examine each model

- Explore possibilities

- Assess prototypes

Framing the problem and developing two competing solutions is the starting point.

The second stage is investigating the options by pitting them against one another. This requires metacognition and empathy to understand the problem, how it was arrived at, and why others may have different viewpoints.

In stages three and four, you stop trying to make sense of competing options and start making your own. These new options take parts from competing approaches to make a better solution than the original.

The third stage is to think about what kinds of integrated answers might be possible. The goal is to develop a variety of potential solutions.

The last stage is to evaluate the prototypes by testing the solutions, ideally with actual customers or users who experienced the problem. This step aims to produce a solution that is elegant in concept and workable in practice. And then put it to use. Creating new solutions and testing them with users requires creativity, empathy, and teamwork.

The Integrative Thinking Process

1. Frame the problem and articulate two opposing solutions.

First, define a problem worth solving. A clear problem statement is fundamental to the exercise. Problems worth solving are simply those that matter to the problem-solvers. It doesn’t have to affect the state of the world.

- Write a brief statement that summarizes the problem. You can always revise it later. Make sure your team understands and is entirely behind solving it.

- Don’t obsess over wording, but avoid biased language. Consider starting your problem statement with “How might we…?” in place of judgmental language such as “Can we…?” or “Should we…?” Words like “might” defer judgment and expand possibilities.

Second, make it a two-sided dilemma by identifying two extreme solutions. Extreme alternatives naturally encompass a large number of alternatives between them. And the tension between these opposing options will generate insights that lead to new possibilities.

- Describe each option in enough detail for the team to agree on its core elements. Explain each option and its application in a few sentences, bullet points, or pictures. Ensure everyone is talking about the same thing, understands the tension between ideas, and sees the choices in stark contrast.

2. Examine the options.

Identify the points of tension, assumptions, and cause-and-effect forces in the options. You’ll use the tension between options to create new or better options.

Use exploratory questions to start a conversation with your team about the options, their benefits, and their differences. Comparing the options:

- What do you value most about each? What are the preferences of the different people on your team? These preferences can be used to create different solutions later.

- What assumptions underpin the options? How would you view the option if the assumptions proved false?

- What are the cause-and-effect relationships at work? These relationships can help illuminate new options as well as anticipate downstream effects.

Identify elements you want to keep as you create new answers.

If examining options reveals a more worthy problem to resolve, reframe the problem.

3. Explore the possibilities; develop prototype solutions.

To generate possibilities, explore how to take the best parts of the options to build a new option that solves the problem better. Here are some guiding questions:

- Hidden Gem. How could we make a new option by taking the one best part from each opposing option and discarding the rest? (Use one element from “A” and one element from “B” and discard what’s left of the original options. )

- Double Down. What if we choose one option but add the best key element from the other? (Combine all of “A” with the one element you most care about from “B.” Essentially, improve “A” with the best element of “B.”)

- Decomposition. How could we divide the problem so each option could solve a distinct part? (Break the problem into two discrete parts. Apply “A” to one part and “B” to the other.)

Generate several ideas that are better than the original options.

4. Assess the prototypes.

Refine and test your options until you find the one that works best for you. Shift your mindset from thinking to doing. Gather data about what works, why, and under what conditions.

The best test is with actual customers to see how each option solves the problem under working conditions. Use stories, images, or physical models to make the solution tangible and the test accurate.

After prototyping and testing, the team makes a choice based on the analysis. For this, genuine consensus is required.

A Better Way to Make Choices

In sum, integrative thinking is making better choices by creating them:

- Agreeing on the problem worth solving;

- Articulating opposing solutions and diving deep to understand them;

- Creating new options that contain elements of the original alternatives but are better than either one; and

- Generating confidence and enthusiasm for a solution by conducting tests with customers or end users.

And throughout, being aware of your thinking, encouraging others to share their perspectives, and supporting creative thinking.

Becoming a Better Decision Maker

It starts with your stance: “how you see the world around you, but also how you see yourself in that world.” Hilary Austen calls this “directional knowledge” that involves identity and motivation. Stance is mainly implicit, deeply ingrained, and frequently taken for granted.

Stance and outcomes are linked. Your stance plays an important, albeit underappreciated, role in your life. Your perspective on the world and your role in it motivates you to act in specific ways (and not in others). These actions then influence your outcomes.

Stance is more implicit than reasoning, so it rarely surfaces in our awareness where we can examine how it affects our thinking and our outcomes. That requires a more diligent effort.

You can change your stance through feedback and learning.

Use a richer source of learning.

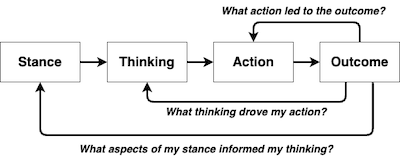

The book uses versions of double-loop learning to help us understand how examining our thinking and our stance can lead to better outcomes.

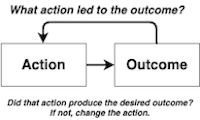

1. Single-Loop Learning–Immediate Feedback

Single-loop learning is the default learning style for most of us. The operative question is, “what action led to the outcome?” And when the action doesn’t produce the desired outcome, we usually change the action rather than question our reasoning, why we chose that action, how we applied that action, etc. A learning focus on improving the action is okay; it’s just limited.

Single-loop learning is shortsighted. It places too much emphasis on the immediate cause–our actions–and not enough on the more powerful ultimate cause–our thinking that led to those actions.

Stopping at single-loop learning gets us stuck, confused, and lost.

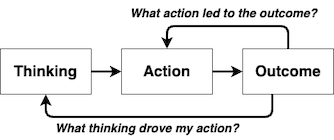

2. Double-Loop Learning–Examining Our Thinking

Double loop learning has two operative questions: ”What action led to the outcome?” and “What thinking drove that action?”

Double-loop learning adds the all-important “why? question. This requires us to step back and examine the thinking that led to our action and ask “why?” It’s helpful to think like a journalist and find out why those actions were taken, not just what happened and how. Learning begins when you discover why.

3. Triple-Loop Learning–Examining Our Stance

Triple-loop learning for better decision-making has three operative questions: “What action led to the outcome?” “What thinking drove my action?” and “How did my stance influence my thinking?”

Understanding outcomes requires considering both thinking and stance, especially if you want different outcomes in the future.

Besides being a better decision-making process, employing integrative thinking can help us develop a more productive stance about making decisions.

Develop an Integrative Thinking stance.

There is no one best stance–no single, most successful way to be in the world, but rethinking our stance can lead to better decision-making.

Rethinking your stance involves reassessing how you view the world and how you see your role in it. Below are six things the authors encourage you to consider.

The world is…

- Complex, so we understand it through simplified models. These models are constructions and are (at least a little bit) wrong.

- Understood in different ways by different people. These opposing ways of seeing the world represent an opportunity to improve our models.

- Full of opportunities to improve our models over time, as long as we are open to the idea that a new answer is possible.

Therefore, my job is to…

- Get clear about my thinking, and open it to inquiry so that I can better understand my model of the world.

- Genuinely inquire into opposing views of the world to understand and leverage those opposing models.

- Patiently search for answers that resolve the tension between opposing ideas and create new value for the world.

These six stance elements can significantly impact your outcomes over time. Don’t worry if this doesn’t resemble your current stance. Practicing integrative thinking will help you develop your own version over time.

Book details and where to buy it:

Get the book on Amazon: : e-book | Audio | Print (affiliate links*)

Amazon rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars

Goodreads rating: 4.0 out of 5 stars

Page count: 297

Publication date: August 29, 2017

Author website: rogerlmartin.com

*These are affiliate links. We may receive a small commission from Amazon on your purchase at no additional cost to you.