How to Take Smart Notes: One Simple Technique to Boost Writing, Learning and Thinking

by Sönke Ahrens

Better note-taking leads to better thinking, learning, and writing. That’s the premise of How to Take Smart Notes. But it’s not the disposable notes that most of us take, nor is it the haphazard note-taking process many of us use.

You’ll be introduced to Niklas Luhmann’s slip-box note-taking method. Luhmann, a lawyer/civil servant turned university professor, by the end of his career, had published 58 books and 400+ articles aided by his slip-box. (Some sources say 70 books, including those published posthumously from work in progress.) He wasn’t just prolific but influential. He’s considered one of the most important social theorists of the 20th century and a prominent thinker on systems theory.

Luhmann realized traditional note-taking methods, commenting in the margins and organizing notes by source, didn’t work. The notes were scattered and passive; they didn’t interact with each other. As a result, the whole was not greater than the sum of the parts.

His Zettelkasten system (German for “slip-box”) was born in response. Rather than keeping notes tucked away with their respective texts or in notebooks, he collected them in one place, in something that looked like the old-fashioned library card catalog. He captured ideas (in his own words) on slips of A6 paper (about the size of a 4X6 index card) and filed them in a single location, a slip box. But the ingenious parts of his system were, as we’ll learn, the type of notes he wrote and his filing and indexing system.

Over time, his slip-box became a rich resource with over 90,000 notes. But, more than a simple collection of notes, it became an extension of Luhmann’s brain. Besides being a reliable, external memory, it was a research partner—a thinking tool for building lines of thought, generating new ideas, and getting a head start on the writing process.

How to Take Smart Notes has three parts: Part 1, the Introduction, covers what you need to know, do, and have in place to implement the slip-box method. Part 2, The Four Underlying Principles, outlines the thinking underpinning this approach and its benefits. Part 3, Six Steps to Successful Writing, addresses how to incorporate the slip-box method into your writing process.

The author, Dr. Sönke Ahrens, is a writer and researcher in education and social science. He served as a university professor for the philosophy of education.

The note-taking method described in this book isn’t suitable for everyone. Check out these resources here and here to learn more about the different types of note makers: “students,” “librarians,” “architects,” and “gardeners.”

The Smart Notes approach will appeal to “gardeners,” who enjoy growing their knowledge garden. However, there are “librarians” who tend to create notes project-by-project. And there are “architects” who enjoy tinkering with their system as much as its contents. Most of us are “students,” minimalist, practical note takers who take outcome-oriented short-term notes. But, whatever your style, this book will help you retain more of what you read, sharpen your thinking, and build a bank of knowledge assets that will help you succeed. Also, check out my summary of Building a Second Brain which describes a more universal approach to note making.

This summary reflects my takeaways from a useful book I recommend to others. Reading a summary isn’t a substitute for reading the book. There’s much more than I can cover here. Plus, this is my interpretation. If these ideas resonate with you, I encourage you to get a copy from your favorite bookseller. Here are the Amazon links: e-book | Audiobook | Print

Unless otherwise noted, all quotes should be attributed to the book’s author.

This summary is based on the 2022 Kindle edition.

SUMMARY

Niklas Luhmann’s Zettelkasten System

Luhmann’s system was paper-based and consisted of:

- The slips–ideas captured in notes written on A6 paper, roughly the equivalent of a 4×6 index card.

- Three types of notes:

- Fleeting notes captured his thoughts and ideas at the moment.

- Literature notes recorded interesting points from his reading, including bibliographic information on the source.

- Permanent notes, partly derived from the fleeting and literature notes, in which he developed and elaborated on ideas, using his own words to record his thinking for future use.

- Two slip-boxes–one for his permanent notes and the other for his literature/reference notes.

- A numbering system that supported indexing and linking the ideas that the notes contained.

- A filing system organized the slips according to the idea’s content and what context he might use or rediscover the idea later. He used a branching system that made it visually apparent where the ideas were clustering.

- An indexing system that made every card an access point for related ideas and clusters of ideas.

- A workflow comprising:

- Reading

- Note-taking and permanent note-making

- Idea organizing, elaborating and linking

- Writing and publishing

Luhmann’s system was an enabling environment that:

- Extended his brain, providing reliable long-term memory that stored information faithfully and supported easy retrieval.

- Became his thinking partner. He used it to develop lines of thought, cluster ideas, and discover new connections.

- Freed his brain to do what brains do best: see patterns, make creative connections, generate and answer questions, develop new understandings and theories, zoom out to grasp the big picture, and zoom in on the details.

He switched between multiple projects as his interest or energy waned. He followed the most interesting, promising path–the path that offered the most insight and kept his interest and energy high, thus keeping him productive.

Why create a slip-box system?

It’s a learning tool. Besides the benefits listed above, simply using the slip-box involves processes that are learning methods that support long-term retention, including:

- Elaboration–Connecting ideas to prior knowledge and exploring the broader implications.

- Spaced repetition–Retrieving ideas at different times.

- Variation–Seeing ideas in different contexts.

- Contextual interference–Rediscovering ideas you weren’t expecting.

- Retrieval–Mindful retrieval and re-discovery of ideas.

- Deliberate practice–Building skills in capturing and developing ideas.

- Self-testing–Continuous feedback on your ability to get to the gist of things and get the thought down on paper.

It eliminates having to face the “blank screen.” The slip-box provides more than isolated facts; it provides lines of developed thought. It’s far easier to elaborate on a line of thought than to start one. Capturing essential ideas, and organizing and managing those ideas, make all the difference when we sit down to write.

It supports creativity. A search through the slip-box will expose you to related notes you did not expect, leading to insights and innovations.

Its value compounds with added notes. Adding more content creates more connections, making it easier to add new entries smartly and get valuable suggestions back.

How to Take Smart Notes

The tools required are minimal:

- Something to write with–a pen and a stack of index cards, or a digital note-taking app.

- A slip-box–a physical box suitable for your cards or a digital app capable of linking notes. (See the links at the end of this summary.)

- A reference management system–a second physical slip-box, space within your note-taking app, or a dedicated reference manager. (See links below.)

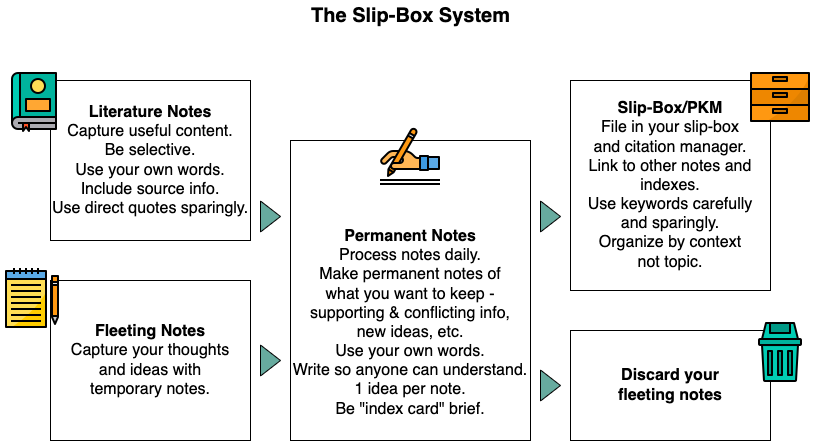

It’s based on three types of notes:

- Fleeting notes are reminders of those ideas that come to you while doing something else. Jot down enough so that you can remember the gist of it later. They don’t have to be elaborate–may be a word or short phrase–just enough to remind you of the thought later as you add permanent notes to your system. Your fleeting notes should be processed within a day or so.

- Literature notes capture the main points when you read something interesting. Write them in your own words and ensure you’ve captured both the idea and its context. Be selective about what you capture, and keep your notes brief. Use direct quotes sparingly. Note the source.

- Permanent notes are interpretations and elaborations of the ideas from your fleeting notes and ideas you are developing.

Permanent notes go into the slip-box. File literature notes in a second slip-box or a citation manager. Discard fleeting notes after the permanent notes are created.

Questions to decide if your idea is permanent-noteworthy:

- Does this add to, correct, support, or contradict current knowledge?

- By combining these ideas, can I create something new?

- Does this provoke new questions?

- Will it otherwise be useful or interesting to me in the future?

Write your permanent notes so they’ll make sense to your “future self.” Permanent notes should be brief but complete. Write them carefully to capture your exact thoughts, ideas, or opinions. Each note should contain a single idea. Use complete sentences, include references, and elaborate on the idea enough that you’ll understand it in the future. Write them as if you are writing for someone else.

Use your own words. There’s a temptation to copy and paste from the source material, especially when using digital tools. For learning and future publishing purposes, it’s better to translate the idea into your own words. You’re building a body of your thinking, not an archive of other people’s thoughts.

Writing permanent notes is thinking–thinking in dialogue with the ideas already in the slip-box–extending lines of thought, amplifying or challenging them, or approaching them from another angle.

Organize notes by context, not topic. How a note connects to other ideas determines its value. Organize your notes according to your interests, ideas, and questions. Ask yourself: “Where might I use this note? How does it relate to other ideas?”

Use keywords sparingly. Choose them carefully. Using too many keywords makes managing your notes difficult, especially if you are working on paper. Avoid generic keywords and don’t base them on the source’s context. Instead, base your keywords on your context—your specific interests or lines of thought as well as how you might use or find that note in the future.

Link each note. Every permanent note should be linked to at least one other note and a summary note or index. (Zettelkasten-friendly apps have tagging and two-way “back linking” features that facilitate this.) Each note should be considered a point of entry into your slip-box, and its links are there to help you navigate through it to see what ideas emerge.

Create index notes that reflect lines of thinking that interest you or that you think might be useful in the future. Outline these on an overall index. Indexes can serve as a starting point for developing projects–writing and otherwise.

Taking smart notes is straightforward, but its simplicity can be deceiving.

- The typical note-taking process is haphazard. We do what makes sense at the moment, usually without an eye toward how we will use them. We underline a passage here and record a thought there, which leaves us with nonuniform notes in various locations. Just returning to an idea is a taxing search process.

- Standardizing the notes makes it possible to gather them in one location, making them more accessible. Plus, they are organized to interact–creating clusters of thinking and lines of thought. Whether we use physical index cards or a digital app, our notes can go from an assortment of other people’s ideas scattered across various books and other locations to a concentrated, accessible repository of our own thinking.

Work as if “writing is the only thing that matters.”

You’ll improve your reading, thinking, and other intellectual skills even if you don’t write a single manuscript line.

- You’ll read in a more engaged way. You’ll be more focused on the most relevant aspects. Instead of passively highlighting, you’ll create notes that elaborate on the meaning behind your reading, making it more likely you’ll remember.

- You’ll have an obvious purpose for giving attention to other media or attending talks. You will be more engaged, focused, and selective.

No one starts from scratch. Sitting down to write doesn’t involve ideas pulled out of thin air. There’s always some background. Some prior work. Some thinking precedes the decision to write. “Every intellectual endeavor starts from an existing preconception.”

- The slip box jump-starts the writing process. Looking into the slip-box, we don’t just see a collection of nicely arranged notes; instead, we see built-up clusters of ideas that can serve as possible topics. And every idea that emerges from the slip box comes “naturally and handily with material to work with.”

Let the work carry you forward. Good workflows become virtuous cycles: positive experiences motivate us to embrace the next task. As a result, we become more productive and better at what we do, which furthers our enjoyment of the work. And the cycle continues.

- The dynamic of working with the slip-box can have intrinsic and extrinsic rewards. The impact on our intellectual growth and mastery has its intrinsic rewards. And we are likely to see extrinsic rewards from our increasing productivity and the growing value of our contributions.

- The more you add to the slip-box, the more you can draw from it. Similar to how our brains work, the slip-box’s value increases with complexity–more ideas mean more connections between ideas and more developed lines of thought. Adding more content makes it easier to add new entries and receive valuable suggestions.

Creating notes and connecting them isn’t maintenance; it’s asset building. The search for meaningful connections is a crucial part of the thinking process. Rather than figuratively searching through our memories, we comb through the slip-box to create links. Working directly with well-curated notes ensures that our thinking and writing results in well-formed ideas grounded in facts and supported by documented references where needed.

If the Smart Notes method becomes a part of your routine, you won’t have to think about what to write or how to start. Follow your interests, take notes while reading, and convert the most meaningful ideas into permanent notes. Then look for patterns and clusters in your notes, arrange your notes into projects as writing ideas emerge, and then write.

Learn more about Niklas Luhmann and Zettelkasten:

Tools:

Note-taking apps with linking and tagging features:

- Obsidian (free with paid add-ons), https://obsidian.md

- Roam Research (subscription), https://roamresearch.com

- Zettlr (open source), https://www.zettlr.com

- Notion (freemium), https://www.notion.so

- logseq (free, pay what you want), https://logseq.com

- The Archive (paid), https://zettelkasten.de/the-archive/

Citation managers:

- Zotero (open source), https://www.zotero.org

- Endnote (paid), https://endnote.com

Book details and where to buy it:

Buy the book on Amazon: e-book | Audiobook | Print (affiliate links*)

Amazon rating: 4.4 of 5 stars

Goodreads rating: 4.2 of 5 stars

Page count: 212

Publication date: March 8, 2022

Author website: https://takesmartnotes.com

*These are affiliate links. We may receive a small commission from Amazon on your purchase at no additional cost to you.